Negative Nostalgia: How We Stopped Believing in the Future

Written by Lina Leskovec

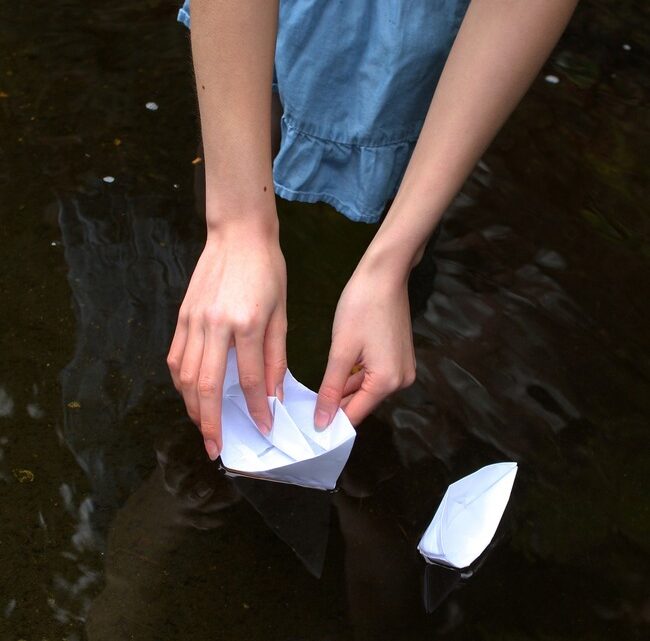

Photograph by Ashley Miya

Walking down the street in any area that would pejoratively be described as gentrified, you see them everywhere — charity shops, vinyl stores, antiques and antiquarians. It seems like we live in an age of nostalgia. This is not a new phenomenon, but it is definitely one which has undergone a substantial transformation. Our understanding of nostalgia started out as a diagnosis of a serious disease and was transformed into a warm and fuzzy feeling of reminiscing over the centuries.[i] It has been researched as a form of escapism that can stem from negative emotions on a personal level, although it is usually presented in connection to positive emotions.[ii] Collectively, we understand nostalgia as a mostly aesthetic phenomenon. However, are warm and aesthetic connotations still the main part of the nostalgia we collectively encounter in this nostalgic age? Or has it transformed into a more negative and anxious feeling that permeates our social structures and language? Recent developments suggest the latter.

There is nothing unique about living in a nostalgic age. In recent history, both the 1970s and the early 2000s have been branded as such. What ties these periods together is that they were times of crisis, either in an economic sense with stagflation of the seventies, or in a sense of social uncertainty, which accompanied the Y2K hysteria. It seems like we have found ourselves in another crisis, or rather several crises, and this brings with it a longing for a simpler past. Nevertheless, the current situation is distinct. Current-day nostalgia has a much stronger social aspect. Although rejection of modernity necessarily includes at least some form of rejection of social change, which was also the case in twentieth-century, nostalgia is becoming less aesthetic and more political. But before I tackle this new manifestation, let me briefly trace back the history of nostalgia.

It started out as a serious medical condition. Seventeenth century Swiss doctor Johannes Hofer observed uprooted soldiers, migrants, and slaves and determined that their longing for a return to the homeland could have dire medical consequences. He diagnosed the disease of nostalgia, a disease so dangerous it was sometimes deadly. Hofer’s nostalgia did not have any connotations of a warm remembrance of an idyllic youth, neither did it have an aesthetic element.

That all changed in the nineteenth century when the medical field lost interest in the term and nostalgia was taken on by artists. The romantic period de-pathologised nostalgia and transformed it into a positive, if slightly sentimental, emotion. Most importantly, nostalgia gained an aesthetic component which has been the key in our understanding of the term ever since.

In a way, nostalgia is an aesthetic thing. We cannot really reject modern life or return to the past — we can only use outdated technology, appreciate historical paintings or dress ourselves in hand-me-downs. Indeed, the aforementioned signifiers — charity shops, vinyl shops, antiques — are purely visual. Yet, longing for the past brings anxiety about the future and it seems as if this anxiety is overtaking the visual element in modern day nostalgia as well.

Hope for the future is gone. If we observe mainstream discourse, this sentiment is shared by all sorts of, otherwise conflicting, political and social groups. On one hand, there is the fear of a disappearing ‘way of life’. The only solution that is presented as a counterforce is a return to a previous ‘way of life’, no matter how vague this term is. Trump did not want to make America great, he wanted to make it great again. Brexit supporters did not want to gain control over Britain, they wanted to take it back. There is no room for innovation or reorganisation, only for a return. A rejection of progress and a fear of societal degeneration is not something the modern far right has come up with. Early twentieth century fascist ideologies shared those same principles, but their story was more complex. While fascism and Nazism labelled everything from modern values to modern art as degenerate, there was simultaneously a surprisingly great enthusiasm for modernity in both movements. Technological development and certain types of avant-gardes (futurism in Italy and expressionism in Germany) were seen as key in the movement. Society was in need of a fascist rebirth, not simply a return to the past.[iii] In this way, modern far-right movements offer a much more nostalgic solution.

On the other hand, things are not that wonderful on the left either. Future prospects are increasingly tainted by the growing danger of climate change. Even though the issue has been in the public consciousness for a couple of decades, there has been little counter action. This, combined with the constant reminders that now is the last moment to act before our planet is beyond the point at which it can be saved, is leading to the spread of climate ‘doomism’. Climate doomists believe that climate change cannot be stopped. New technology is associated with new ways of exploiting the environment instead of new solutions.[iv] Escapism can be a coping mechanism and the only place or time to escape from climate change is the past. Nostalgia as escapism was previously seen as more of a personal issue, now it has taken on a group identity.

Climate ‘doomism’ is widely criticised and is seen as dangerous to counter-climate-change action. It has developed into a sort of subculture which can have dire consequences both for the individuals who participate in it and on the fight against climate change. It thrives in online environments and creates more opposition from climate scientists, on top of the already existing, climate-denying one. Yet, it is not difficult to see why looking into the future or living in the present is grim when we are constantly faced with the decaying of our planet. And even if we do not take it as far as ‘doomism’ does, the chances that significant environmental action is approaching anytime in the near future are not looking good.

Figure 1: Signs from a climate protest in Bonn, Germany in 2019. Photo by Mika Baumeister from Unsplash.

We have transformed nostalgia. Sentimentality has been replaced by nationalistic politics or collective anxiety. However, maybe the loss of hope in the future is not such a bad thing. In between the periods of nostalgia in the twentieth century were periods of idealism. The post-war period was a period of optimism and, after the fall of communism, followed a blind faith in global capitalism, famously branded by Fukuyama as “the end of history” – meaning an end to the ideological struggle and the triumph of western liberal democracy.[v] Idealism is surely less anxiety-inducing preference to live by, but it can make us uncritical and impractical. If we have an overly positive outlook and presume that a good future is inevitable, the incentive to fight for a better world diminishes. The belief that the future is not given, but rather something we have to work hard for, can lead us to want to better assess the decisions we make today. Svetlana Boym develops this idea when she claims nostalgia can be coeval with modernity, not an antithesis to it.[vi] It can help us examine our current issues through a historical lens and thereby helps us avoid the pitfalls of believing society is necessarily always progressing. This re-characterisation seems to be a good middle ground – if we must live in an age of nostalgia, let us make the most out of it.

Endnotes

[i] Thomas Dodman. “Nostalgia, and what it used to be”. Current Opinion in Psychology 49, (February 2023): 101536.

[ii] David B. Newman and Mathew E. Sachs. “The Negative Interactive Effects of Nostalgia and Loneliness on Affect in Daily Life”. Frontiers in Psychology 11 (September 2022): 2185.

[iii] Mark Antliff. “Fascism, Modernism and Modernity”. The Art Bulletin 84, no. 1 (March 2002): 148-169.

[iv] Osaka, Shannon. “Why Climate ‘Doomers’ are Replacing Climate ‘Deniers’”. Washington Post, March 24, 2023.

[v] Francis Fukuyama. “The End of History?”. The National Interest, no. 16 (Summer 1989): 3-18.

[vi] Boym, Svetlana. “Nostalgia and Its Discontents”. The Hedgehog Review: Critical Reflections on Contemporary Culture, Summer 2007.

Lina Leskovec is a second year political science student at UvA. Before moving to Amsterdam, she lived in Slovenia. Specialising in political theory, she has an interest in philosophy and its practical application. Other than that, she enjoys reading, art and chess.

Ashley Miya is a third year BA student at Seattle University studying Photography with a minor in Studio Art. She has worked in Social Media for multiple platforms, is a current photography intern and does private and commercial photography. Ashley loves travel, culture, and building community. One of her favorite travel experiences was the opportunity to teach underprivileged children in Myanmar. In her free time she is often found exploring art, music, dance and just being creative.